AESA PROGRAMMES

- Building R&D Infrastructure

- Developing Excellence in Leadership, Training and Science in Africa (DELTAS Africa)

- Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa)

- Africa’s Scientific Priorities (ASP)

- Innovation & Entrepreneurship

- Grand Challenges Africa

- Grand Challenges Innovation Network

- Rising Research Leaders/Post-Docs

- AESA RISE Postdoctoral Fellowship Programme

- African Postdoctoral Training Initiative (APTI)

- Climate Impact Research Capacity and Leadership Enhancement (CIRCLE)

- Climate Research for Development (CR4D)

- Future Leaders – African Independent Research (FLAIR)

- Critical Gaps In Science

- Clinical Trials Community (CTC)

- Community & Public Engagement

- Mobility Schemes: Africa-India Mobility Fund

- Mobility Schemes: Science and Language Mobility Scheme Africa

- Research Management Programme in Africa (ReMPro Africa)

- Science Communication/Africa Science Desk (ASD)

- Financial Governance: Global Grant Community (GGC)

- AAS Open Research

- CARI Programmes

- Evidence Leaders Africa (ELA)

News

NTDs: Increased Effort Needed to Improve Diagnosis of Buruli Ulcer

165

NTDs: Increased Effort Needed to Improve Diagnosis of Buruli Ulcer

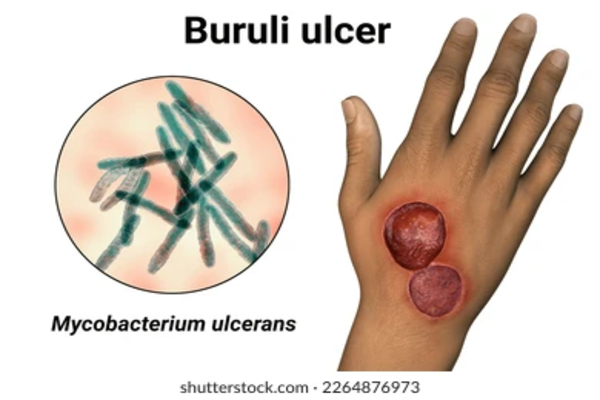

As the World marks the annual Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTD) Day, Buruli ulcer remains one of the most mysterious NTDs globally with the mode of transmission to humans remaining unknown.

Reported in 33 countries across the world, the disease, which mainly affects the skin and bone, is caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans – a germ (bacteria) belonging to the family of those that cause tuberculosis and leprosy, according to Michael Frimpong, a lecturer at the department of Molecular Medicine at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Ghana.

The toxins made by the bacteria destroy skin cells, small blood vessels and the fat under the skin, which causes ulceration and skin loss.

In the past decade, Dr. Frimpong said, more than 95% of all global cases have been reported from Africa, with Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, Nigeria, and Cameroon being the most endemic countries.

“But as the disease affects mainly populations in remote, rural communities, where access to healthcare is limited, the true prevalence of Buruli ulcer is difficult to gauge,” he added.

In Africa, most of the people affected are children under 15, with the NTD often starting as a painless swelling of the affected area, usually the arms, legs, or face, and eventually developing into large ulcers, usually on the arms or legs. The disease may progress with no pain and fever.

Diagnosis remains a challenge

According to Dr. Frimpong, in most cases, experienced health professionals with training in endemic areas can make a reliable clinical diagnosis, but other ulcers such as chronic lower leg ulcers, diabetic ulcers, fungal infections may confuse diagnosis. Thus, standard laboratory methods are required to confirm Buruli ulcer. The best of these is polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

However, despite the World Health Organization (WHO) setting at least 70% PCR confirmation rate as a target for countries to meet, most countries in the African region have not been able to reach this target, he said, adding “rather, the rate of confirmation has been declining due to low PCR confirmation in a number of these endemic countries.”

In 2019, WHO established the Buruli ulcer Laboratory Network (BU-LABNET) for Africa to help strengthen PCR confirmation in endemic countries in the region. The Network is made up of 11 laboratories from nine endemic countries (Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Togo, Liberia, Nigeria and Gabon).

The BU-LABNET seeks to improve quality diagnosis in the African region by ensuring all laboratories in the network utilize standardized procedures for PCR-based diagnostic of Buruli ulcer and implement an External Quality Assurance (EQA) program for these laboratories.

Dr. Frimpong, who is also a member of the expert panel and advisory group, noted that effective and accessible diagnostics is one of the key targets for Buruli ulcer control towards the WHO NTD Road Map 2030.

To improve diagnosis, Dr. Frimpong and his research team in Ghana have developed Buruli ulcer recombinase polymerase amplification (BU-RPA) which can be used in healthcare facilities closer to the patients since the current PCR can only be used in reference laboratories far away from endemic areas.

RPA has emerged as a new technology for the molecular diagnosis of infectious diseases, that can be carried out at room temperature in unsophisticated laboratories.

Dr. Michael Frimpong is a Cohort 2 Fellow of the African Postdoctoral Training Initiative (APTI), a programme implemented by the African Academy of Sciences (AAS) with the support of the National Institutes of Health and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Original article published in Science Africa Limited written by Sharon Atieno, linked here.